5585 Guilford Road • Madison, WI 53711-5801 • 608-273-8080 • Fax 608-273-2021

www.agronomy.org

Twitter | Facebook

NEWS RELEASE

Contact: Hanna Jeske, Associate Director of Marketing and Brand Strategy, 608-268-3972, hjeske@sciencesocieties.org

A tale of two (soil) cities

July 1, 2015--As we walk along a forest path, the soil beneath our feet seems like a uniform substance. However, it is an intricate network of soil particles, pores, minerals, soil microbes, and more. It is awash in variety.

Soil is a living, dynamic substance, and the microbial life within it is crucial to providing plant life with the food they need to grow. The microbes can be bacteria or fungi, but both need space—the pores—for a good living environment.

Soil particles that clump together are aggregates. These are the architectural building blocks of soil. Their presence has a major effect on the behavior of the soil as a community. Multiple processes form the aggregates: cycles of wetting-drying, thawing-freezing, earthworm activity, actions by fungi, and interaction with plant roots.

Soil particles that clump together are aggregates. These are the architectural building blocks of soil. Their presence has a major effect on the behavior of the soil as a community. Multiple processes form the aggregates: cycles of wetting-drying, thawing-freezing, earthworm activity, actions by fungi, and interaction with plant roots.

No matter what formed the aggregates, the pores are affected. So are the microbes living in them.

Sasha Kravchenko, a soil scientist and professor at Michigan State University, studies soils and their pores in different agricultural systems. Her recent work showed that long-term differences in soil use and management influence not only the sizes and numbers of soil aggregates, but also what the pores inside them will look like.

”Pores influence the ability of bacteria to travel and access soil resources,” Kravchenko says. In return for this good home, the microbes help plants access essential nutrients.

“The numbers of bacteria that live in the soil are enormous,” says Kravchenko. “However, if we think about the actual sizes of the individual bacteria and the distances in a gram of soil – that soil is actually very scarcely populated.”

To give an idea of what bacterial communities might look like, Kravchenko gives this image: Imagine looking out an airplane window at night over the Midwest. “It’s mostly darkness with occasional bright specks of lone farms – those represent individual bacteria. Occasionally, you’ll see bright spots of small towns – those would be bacterial colonies. Rarely, you’ll see a larger town or city.”

Kravchenko’s work compared two contrasting agricultural systems. The soil in one system, referred to as conventional in the study, grew crops such as corn in summers. Then the soil was barren from the time of main crop harvest through planting the following spring. The soil in the other system, the cover crop system, had live vegetation year-round.

Kravchenko’s work compared two contrasting agricultural systems. The soil in one system, referred to as conventional in the study, grew crops such as corn in summers. Then the soil was barren from the time of main crop harvest through planting the following spring. The soil in the other system, the cover crop system, had live vegetation year-round.

“These systems have been in place since 1989, so there was plenty of time for the differences between the two systems…to develop,” Kravchenko says. “Most of the changes in soil characteristics do not happen overnight. They need time to develop to such an extent that will be sufficient for researchers to detect those changes using currently available measurement tools.”

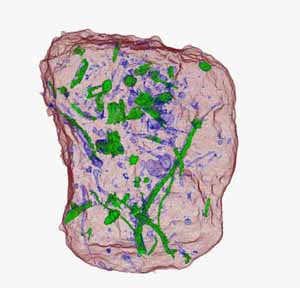

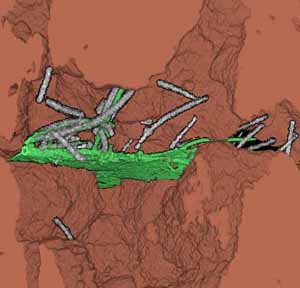

Several surprising observations sprang from the study. First, the aggregates of the two agricultural systems developed different pore characteristics. The aggregates from soil in the cover crop system were more complex and varied in their interior pore structures with more large and medium-sized pores. The conventional system had more small pores spread more evenly through the entire aggregate.

Moreover, microbial communities living in individual aggregates from the same system did not look very much alike. This indicates that an individual aggregate may be a unique system of its own with its own physical build and structure. Much like neighboring cities, an aggregate’s community of inhabitants might be quite different from the community next to it.

Within individual aggregates, different bacteria appeared to prefer different conditions. Many of them liked the areas that had a lot of pores with smaller (30-90 micron) diameter, while others preferred being around large (more than 150 micron) pores. “We don’t know for sure why that was so, but it is likely that pores of this size provided optimal settings in terms of transport of nutrients, fluxes of air and water, and ability of bacteria to reach and decompose plant residues,” Kravchenko says.

These findings highlight the complex interaction of soil particles, pores, microbes, and the plants that grow in them.

Kravchenko and her team used x-ray computed tomography (similar to a medical CT scan). Keeping the aggregates intact gave them an opportunity to view how the soil particles, pores, and particulate organic matter interact in their natural state. “There is only so much we can learn about how soil functions if we work with disturbed soil samples. To get a complete picture we need to look at soil in its intact form.”

The research was published in the Soil Science Society of America Journal.

Soil Science Society of America Journal is the flagship journal of the SSSA. It publishes basic and applied soil research in soil chemistry, soil physics, soil pedology, and hydrology in agricultural, forest, wetlands, and urban settings. SSSAJ supports a comprehensive venue for interdisciplinary soil scientists, biogeochemists, and agronomists.